frontrunning

What Is Frontrunning?

Frontrunning refers to the act of someone executing a transaction ahead of yours to profit from the resulting price movement triggered by your order. This typically occurs while an on-chain transaction is still in the "pending confirmation" stage.

On a blockchain, unconfirmed transactions enter a public "transaction pool" (also known as the memory pool or mempool). You can think of this as a supermarket checkout line: your basket is visible to others before you've paid. Transaction fees—often called gas fees—act like "expedited service fees," with higher-paying users more likely to have their transactions prioritized. If someone notices you're about to make a large purchase, they may buy first, wait for your transaction to drive the price up, and then sell for a profit. This is a classic example of frontrunning.

Why Is Frontrunning So Common on Blockchains?

Frontrunning is prevalent because the transaction pool is public—anyone can observe transactions waiting to be included in a block, and transaction order is typically determined by fee size.

Technically, blockchain networks use a broadcast mechanism that creates an observable window before transactions are finalized. Miners or validators generally prioritize higher-fee transactions. Automated bots further amplify this by monitoring for large trades or low-slippage orders around the clock, creating consistent frontrunning opportunities.

How Does Frontrunning Work?

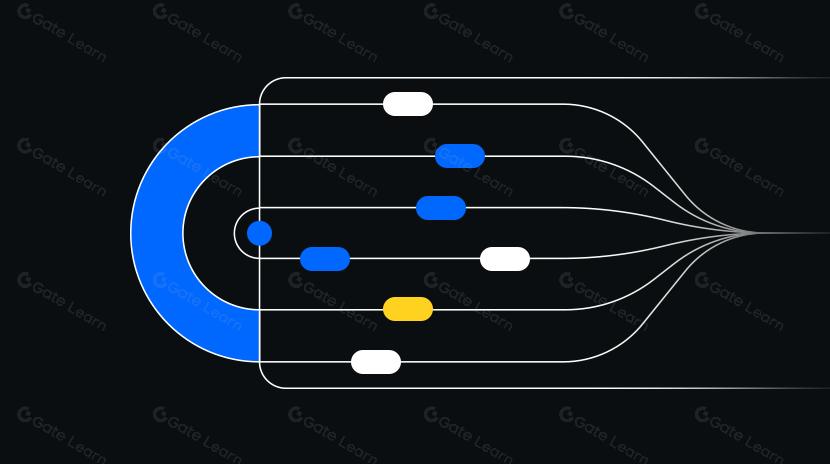

The process of frontrunning typically involves these steps:

- Bots monitor the transaction pool to detect imminent large swaps or price-sensitive trades.

- The bot submits a transaction with a higher gas fee, aiming to execute before you and alter the market price, or set up for a subsequent "sandwich" attack.

- Your transaction executes at the slippage you specified, absorbing the price change caused by the prior trade.

- The bot completes an opposite transaction to secure profits and exit the market. This "buy first – you buy – sell after" sequence is commonly known as a sandwich attack (the bot's trades act as the top and bottom "bread" around your "filling" order).

Examples of Frontrunning on Decentralized Exchanges

On decentralized exchanges (DEXs), the most common frontrunning method is the sandwich attack. For example, suppose you plan to buy $1,000 worth of a token on Uniswap and set your slippage tolerance (the maximum price deviation you accept) at 2%.

A bot detects your order and buys the token with a higher gas fee, pushing up the price. Your order is then filled at a worse rate, consuming your slippage allowance. The bot subsequently sells, profiting from the price increase it just created. This sequence exploits the public transaction pool and fee-based ordering without any need for explicit collusion.

How Does Frontrunning Impact Regular Users?

Frontrunning often results in you receiving worse execution prices, faster slippage consumption, and higher costs. If your slippage tolerance is set too tight, your transaction might fail—and you will still pay gas fees for the failed attempt.

During periods of network congestion, repeated retries and higher fees can drive up actual costs even further. Additionally, bots may model your account’s trading history and public parameters to increase their frontrunning success rate.

How Can You Reduce Frontrunning Risk?

Mitigating frontrunning involves adjusting trading parameters, choosing appropriate channels, and leveraging platform tools:

- Set a reasonable slippage tolerance. Too high makes you vulnerable; too low can cause failures. Adjust based on trade size and liquidity—tighter slippage is advisable for smaller trades.

- Use private transaction channels. These send your transaction directly to block producers rather than exposing it in the public mempool. Examples include using RPC endpoints or routers that support private relays (such as community-referenced channels like Flashbots).

- Employ limit orders and break large trades into smaller batches. Limit orders only execute at or below your chosen buy price (or at or above your sell price), locking in price boundaries and reducing signal strength from large orders.

- Select suitable platforms and tools. Gate, for example, allows use of limit orders, take-profit/stop-loss features, and conditional orders to manage execution prices. Centralized matching occurs within the platform and does not expose your order to the public blockchain mempool—thus reducing frontrunning routes. However, always consider liquidity and fee changes during extreme market conditions.

- Minimize external signals. Avoid disclosing large trades in public communities or broadcasting intentions ahead of time. During volatile markets, avoid peak congestion periods or use more robust routing options.

Risk Note: No strategy can completely eliminate price volatility or execution risk; proper fund management and expectation control remain crucial.

What Is the Relationship Between Frontrunning and MEV?

Frontrunning is a form of Maximal Extractable Value (MEV). MEV refers to additional profits available from strategically reordering or combining transactions within a block—not all forms of MEV harm users; for instance, cross-pool arbitrage and liquidations help maintain fair pricing and lending health.

Malicious MEV often involves sandwich attacks or intentional reordering for profit. As block production and relay mechanisms evolve, ecosystems are experimenting with private routing and batch auctions to mitigate negative effects. As of 2025, public monitoring shows that daily MEV extracted on Ethereum and other EVM chains frequently reaches millions of dollars, fluctuating with market activity and congestion (source: Flashbots and public dashboards, 2025).

Key Takeaways on Frontrunning

Frontrunning stems from public mempools and fee-based prioritization—bots exploit this by positioning trades around yours to profit from price movements. On DEXs, this often takes the form of sandwich attacks, leading to worse execution, failed trades, and higher costs for users. Practical ways to reduce risk include narrowing slippage settings, using private channels, employing limit/batched orders, and leveraging conditional tools on appropriate platforms like Gate. Understanding how frontrunning relates to MEV helps distinguish between activities that maintain market efficiency versus those that degrade user experience—enabling more informed trading decisions.

FAQ

Why do I sometimes experience high slippage when trading on Gate?

Large slippage can result from market volatility, insufficient liquidity, or network congestion. On decentralized exchanges, frontrunners may use higher gas fees to prioritize their transactions ahead of yours, causing your execution price to deviate from expectations. To mitigate this risk, set reasonable slippage tolerances (typically 1–3%) and avoid making large trades during peak periods.

What is the difference between MEV and frontrunning?

MEV (Maximal Extractable Value) encompasses all profits miners or validators can earn by reordering transactions within blocks; frontrunning is a specific form of MEV where miners/bots profit by placing trades immediately before or after yours. In short, frontrunning refers to technical strategies like sandwich attacks that exploit transaction ordering for profit, while MEV covers all such arbitrage opportunities.

How can I avoid frontrunning when trading on-chain with Gate?

Consider these strategies: use private mempools (such as Flashbots) to reduce transaction visibility; split large orders into smaller ones; select highly liquid trading pairs to minimize slippage; and trade during off-peak network hours. Some DEXs offer frontrun protection features—always check platform announcements for support details before trading.

How do frontrunners make money using bots?

Frontrunning bots monitor blockchain mempools for profitable pending transactions. Upon detection, they increase gas fees to get their own trades mined first—buying before your order and selling after it executes for profit (a classic sandwich attack). The profit comes from the price spread caused by your order and your slippage loss.

Why are centralized exchanges (like Gate spot) relatively safe from frontrunning while DEXs are more vulnerable?

Centralized exchanges match orders internally on their own servers; order details are not publicly visible, so miners cannot see or manipulate them in advance. In contrast, DEX orders are transparent on-chain—anyone can view pending trades before they're finalized, allowing miners or bots to adjust gas fees and reorder transactions. This transparency enables decentralization but also increases frontrunning risks—a fundamental trade-off in blockchain design.

Related Articles

Exploring 8 Major DEX Aggregators: Engines Driving Efficiency and Liquidity in the Crypto Market

What Is Copy Trading And How To Use It?